No products in the cart.

Of the many technological leaps characterising the past few decades of human life, few have been as polarising as artificial intelligence—a human-made intelligence intended to match and surpass that of its creators. The idea of AI moved from mythology to science fiction and finally began to take technological shape in the mid and late 1900s. AI systems use algorithms to analyse large training datasets, recognise patterns and categories and make connections within data using machine learning.

The allure of creating an intelligent being from scratch, designed to help humanity, has inspired many utopian visions of a world populated with AI assistants, robots and intelligent machines. Meanwhile, dystopian stories and predictions foreground humanity’s anxiety about being surpassed, replaced, or enslaved by our creations. The reality falls somewhere in between—while AI is closer to a predictive or generative model, modern programmes are learning to write, draw, paint and speak with uncanny verisimilitude and finding applications in almost every industry. AI systems include deep learning Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, which launched its first public demo in November 2022 and image generators like Midjourney and DALL-E.

As art, architecture and design contend with the impact of AI tools, questions are raised about authorship, personhood, ethics and the nature of art, creativity and intelligence. STIR revisits its archives to highlight the work of seven artists who engage with these knotty questions with art made using AI tools. Some artists like Harold Cohen, were ahead of the curve, creating the ‘AARON’ AI program in the 1970s, which paved the way for modern generative image programmes. Others like Yousuke Fuyama are taking AI art to its philosophical extremes by staging an independent conversation between two AI models.

1. Speculative visions of future environments

Indian designer and artist Amith Venkataramaiah intertwines issues of climate change and rapid technological evolution through his generative art series, Plastic Animals (2022). He uses the AI program Midjourney to create speculative images of a future where marine life fuses with plastic waste to survive in the polluted ocean. The ensuing images depict lobsters and turtles with colourful artificial exoskeletons and starfish made of plastic bags fused with their flesh. Midjourney works by interpreting a text prompt from a user using Natural Language Processing (NLP) software to interpret the request, extracting details such as style, colour, objects etc. This is fed to a neural network that compares the request to a vast data set on which it has been trained, extracting and matching elements as required. The model iterates and edits multiple images to refine its output before generating a final image. Realised through this process, Venkataramaiah’s hybrid creatures—half plastic, half-animal—raise larger questions about the fading separation between the natural and human-made world.

2. A pioneer of generative art: Harold Cohen

A pioneer of generative art, British artist Harold Cohen (1928-2016) started as a fine artist before turning to code as his medium. He created the first generative artmaking program, which he called AARON. Developed from the early 1970s to Cohen’s death, it was a precursor to modern AI artmaking models, with its software and dataset coded and curated by Cohen. While it had a smaller dataset compared to its modern descendants, AARON still exercised a great degree of autonomy when creating illustrations within Cohen’s parameters. The artworks produced by AARON were a collaboration between artist and software, as the AI model’s output inspired Cohen’s artistic vision and his feedback allowed the AI to develop in the desired direction. The jagged, abstract compositions and bright colours of Cohen’s artworks were pushed further in his collaboration with AARON.

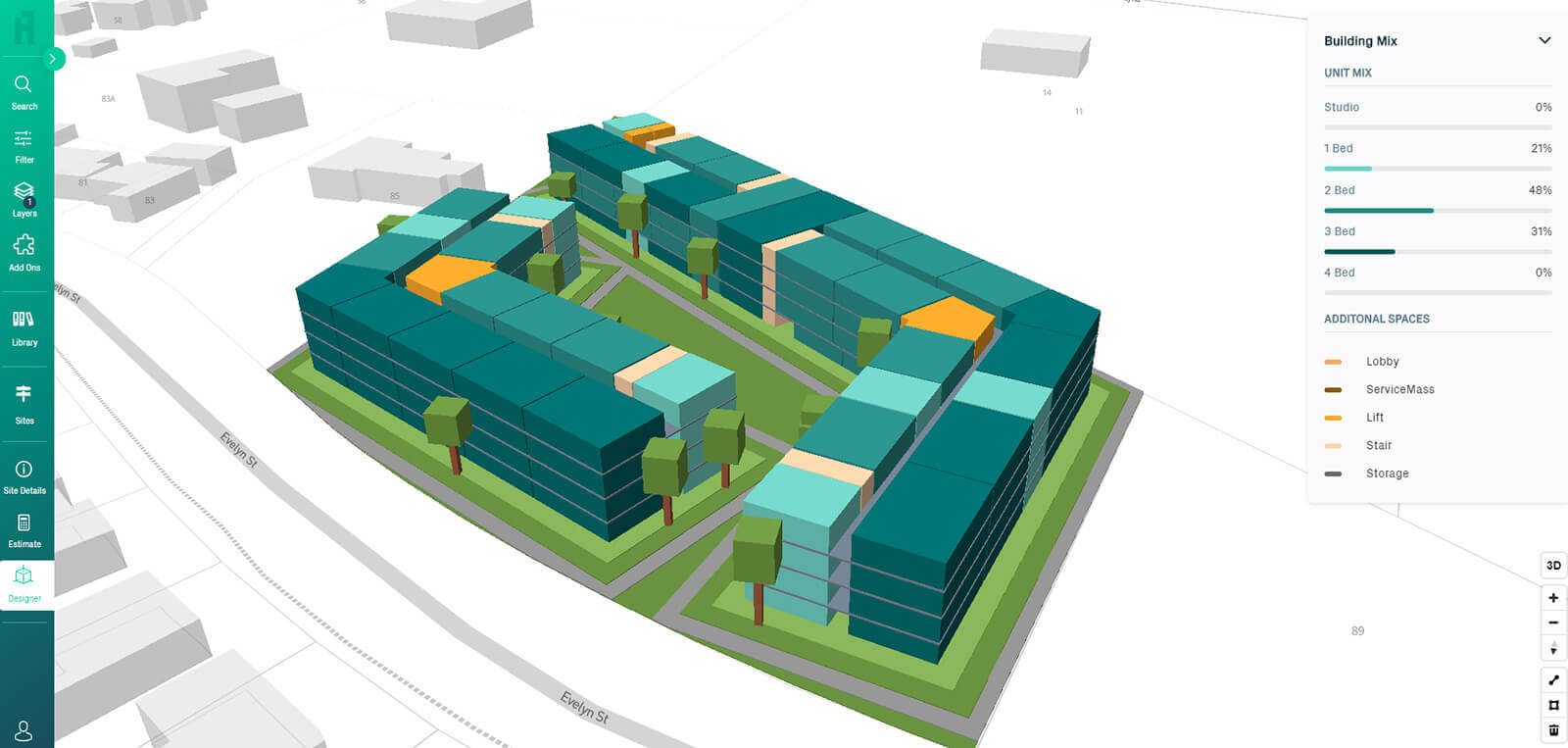

3. AI and parametric architecture

Like almost every industry, architecture is reckoning with the possibilities and flipsides of using increasingly sophisticated AI tools. While some architectural firms like Zaha Hadid Architects are incorporating AI image generators like Midjourney into their design processes, others like British architect Neil Leach are more cautious. Leach writes about AI and architecture, covering both its utopian possibilities, such as the increased democratisation of architecture and design and dystopian ones, like what he terms “the death of the architect”. AI tools use requests and parameters from the end user to generate an output. This is currently limited to 2D images but will develop over the next few years to encompass 3D models and perhaps even technically sound architectural drawings. AI tools open up possibilities for ‘parametric architecture’, wherein experts could design digital tools with variable parameters allowing independent agents to design buildings without extensive training. This could lead to a more democratic, accessible and open-source future for architecture; a big change for the humanistic field and its experts. However, as the possibility of autopoiesis in architecture draws closer, architects and designers must contend with the challenge to notions of authorship.

4. Ronen Tanchum’s digital take on nature

This story from 2024 highlights the work of contemporary artist Ronen Tanchum, who taps into the power of code, 3D simulations and AI to create interactive, generative data art. His work foregrounds the interplay between digital, human and natural worlds. For example, his series Rococo (2022) uses coding languages and custom software to create fusions of artworks stored on a blockchain, generating new digital flowers every 45 seconds. Although nature’s creations inspire him, Tanchum adds his tweaks and embellishments to make them appear more visually interesting and ironically, according to viewers, more realistic. Perach (2021) uses sensors and a biofeedback loop from a plant to transform the life and activity of the plant into music and visuals. Like many other AI artists, Tanchum relies on his experience as an FX technical director to harness the power of computer science for multimedia art.

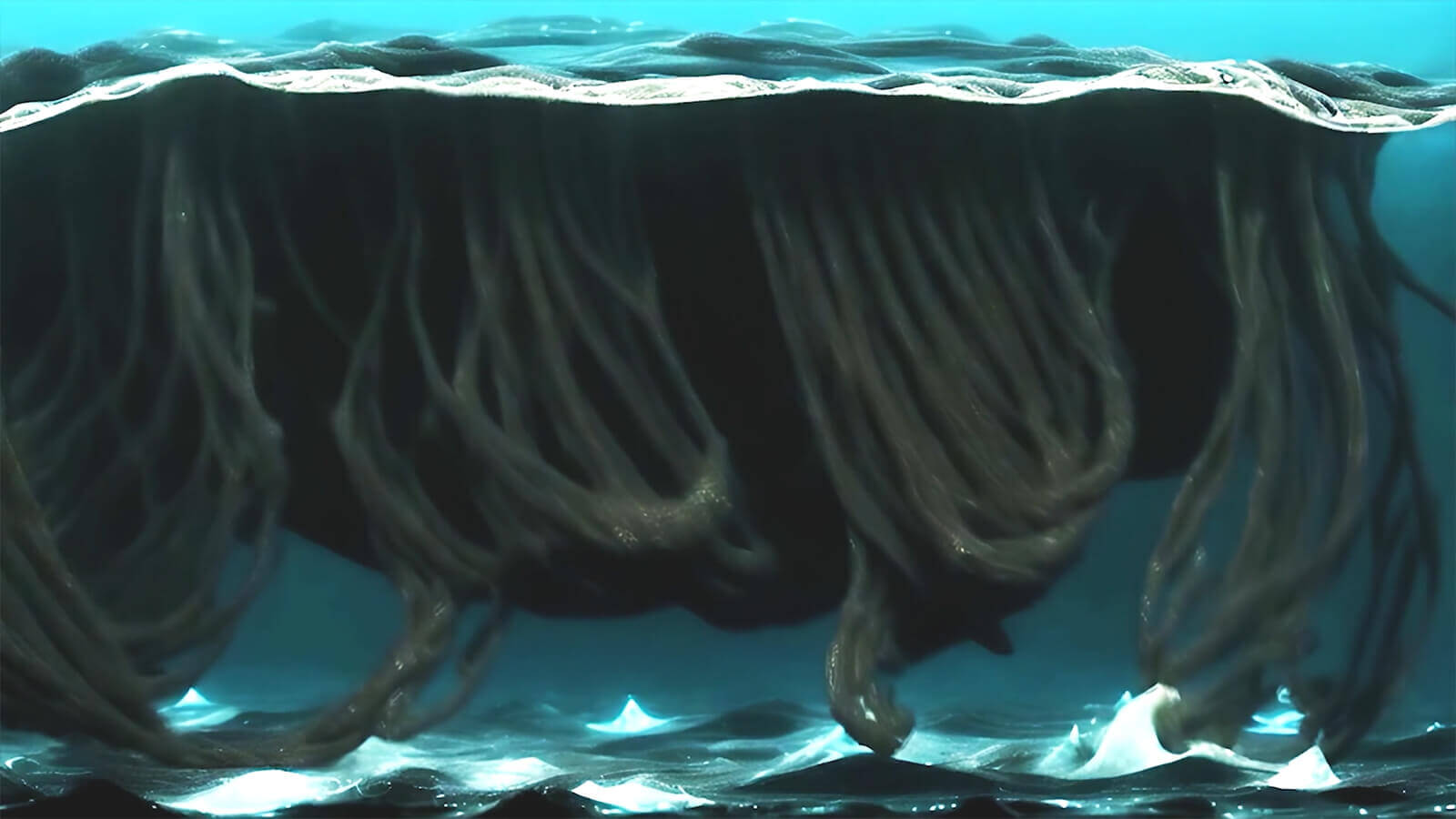

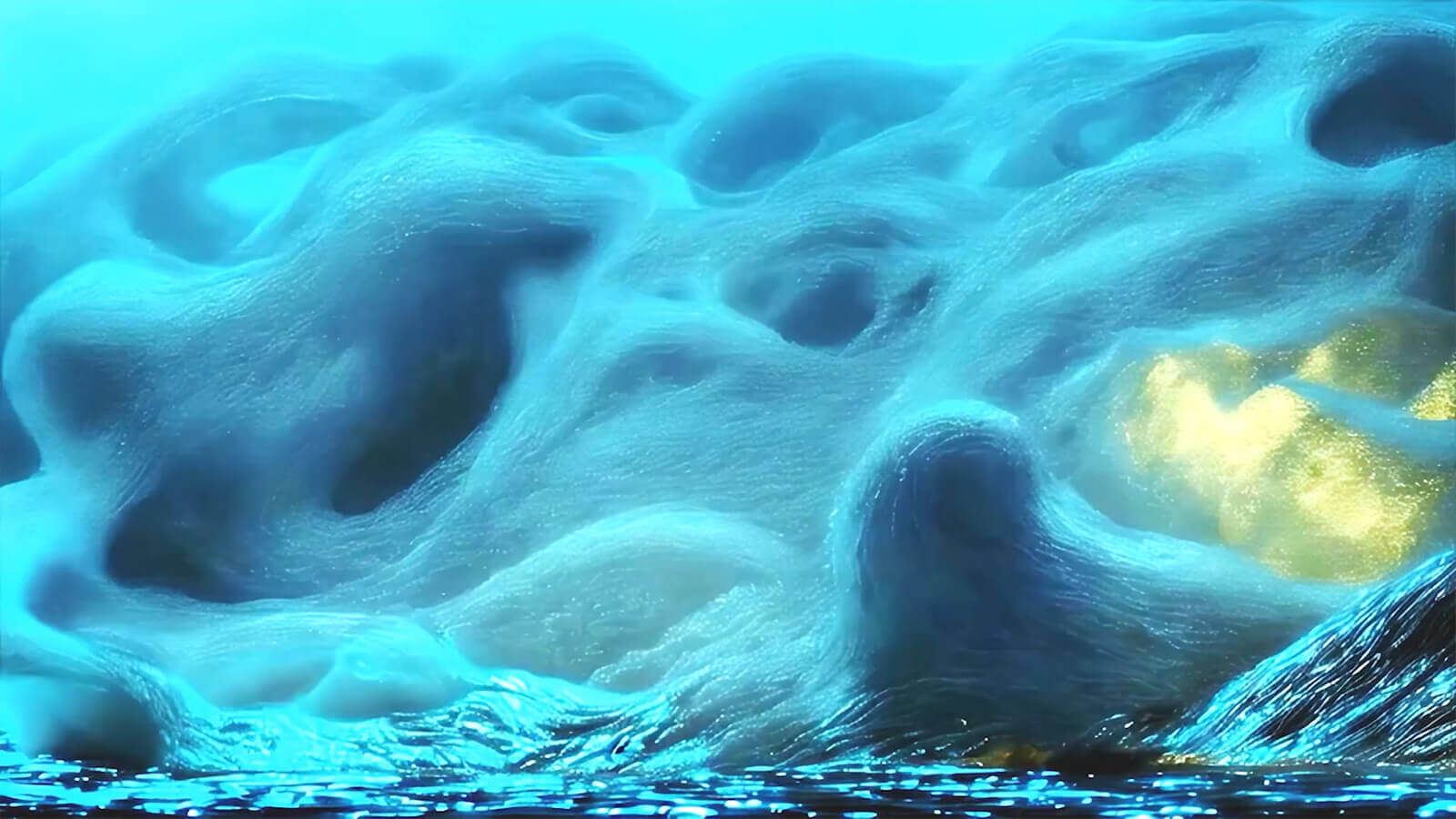

5. Yousuke Fuyama stages conversations between AI models

The Japanese artist, composer and programmer Yousuke Fuyama’s artwork, Land-Venus “La Faille de Signe” Self-Reconstruction (2023), showcases the increasing independence of AI. Fuyama worked with two AI models, feeding the first model raw data from his musical track, Land-Venus and prompting it to generate visuals based on this data. He fed these visuals to the second model, prompting it to generate sounds, repeating the process to create an endless feedback loop. The visuals and sounds that make up the multimedia installation stray far from the original raw data, as the models interpret and mutate each other’s output endlessly. The work’s ability to reproduce itself might draw attention to the consequences of AI development, but Fuyama is optimistic about the role of the artist as a guiding force for another creator – AI, in this instance.

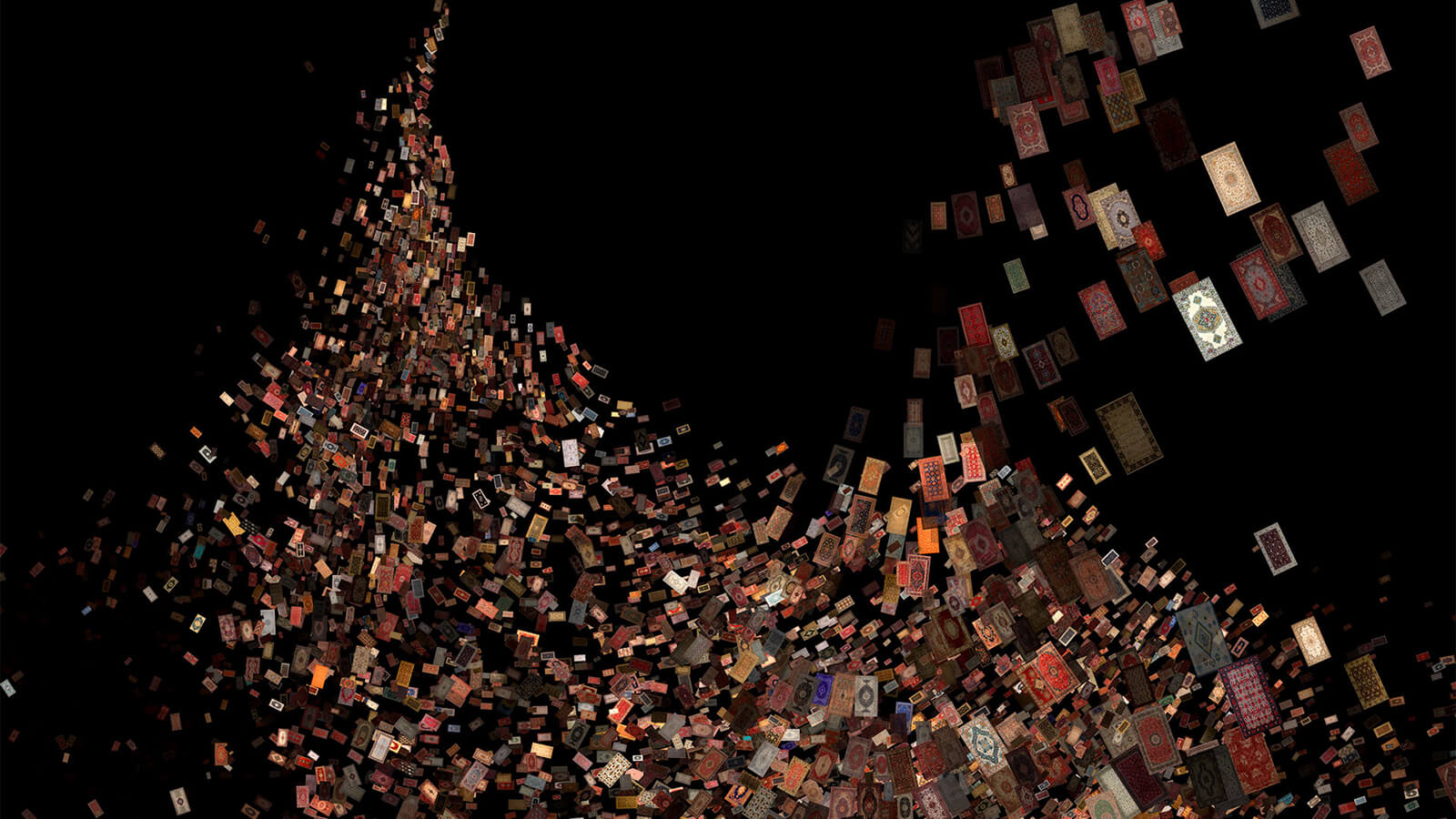

Orkhan Mammadov: reconstructing heritage with AI

The Azerbaijani new media artist Orkhan Mammadov integrates AI programs into his research-based practice to revive traditional art, national identity and heritage in a digital space for a new generation. Mammadov creates large digital tapestries that showcase the craftsmanship and history of the Middle East and the Near East. He created his striking series Revival of Aesthetics (2021) by digitising thousands of traditional carpets and feeding the raw data to a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). A GAN consists of two deep-learning neural networks; one finds patterns and iterates new ones based on its training dataset, while the other evaluates the creations of the first. The result is the GAN’s arguably original interpretation of the traditional rug. In this way, Mammadov blends craft with technology to interrogate how history is transmitted, interpreted, misinterpreted, recast, highlighted and forgotten. The artworks and datasets are stored as NFTs on the blockchain, serving as a decentralised digital archive of Azerbaijani and Middle Eastern traditional crafts.

6. A ballet performance powered by AI

The use of AI is not limited to visual art. Performance artists and musicians like Harry Yeff (a.k.a. Reeps100) are integrating technology with performance—including within forms like ballet. The Oper Leipzig in Germany hosted Fusion (2023), co-directed and co-composed by Yeff. His ‘synthetic voice’ is at the centre of this contemporary ballet performance, created by passing Yeff’s voice through an AI model created in collaboration with Bell Labs, speaking and performing in conjunction with the program to develop a completely new machine-like voice with a much wider range than human voices. He sees the synthetic voice as a cyborg of sorts—a synthesis of human and machine. According to Yeff, his AI program is his digital twin or second self. This ideology is reflected in Fusion, which is based on Plato’s theory of the Divided Self. Yeff’s conception of the second half as a digital twin raises important ontological questions about whether personhood would extend to advanced versions of AI and the implications of an increasingly cyborg vision for the future of humans.

(Text by STIR intern Srishti Ojha)

![14 Best Free AI Picture Generator of 2024 [Tested with Sample Images]](https://mlso5yzhfdmc.i.optimole.com/w:auto/h:auto/q:mauto/https://nuillum.xyz/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/ad8cfa44-242d-4481-a39c-e46242cdde3f.jpg)