No products in the cart.

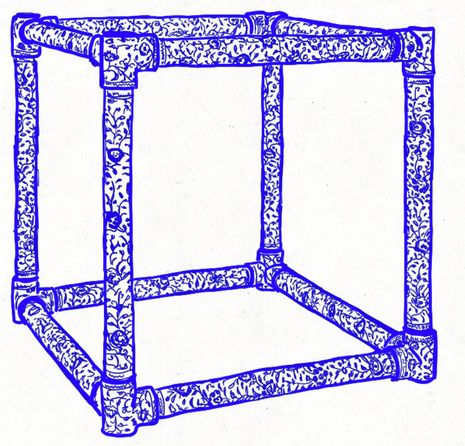

This summer, Ai Weiwei opened his new exhibition, titled Who Am I, in Florence. It marked the last showing of Ai Wei Wei’s work The Porcelain Cube, a porcelain sculpture resembling a cube made of PVC piping, decorated with traditional blue coloured flowers. More than a metre cubed, it was a testament to the skill of porcelain makers, and an interesting reimagining of a thousand-year-old ceramic practice in the context of modern construction, as well as being a beautiful piece of porcelain itself. The Porcelain Cube was destroyed by Vaclav Pisvejc, a 57-year-old Czech man, during the private viewing. Pisvejc pushed over the artwork before being tackled by bodyguards, but the damage was already done. The shards were cleaned away and replaced with a life-size print of the artwork for the duration of the exhibition.

“Acts of destruction which have artistic and historical significance can warp the meaning of the artwork”

The vandal, Vaclav Pisvejc, regards this destruction as art making. In fact, the smashing of The Porcelain Cube comes after a series of acts of vandalism by the artist: setting fire to a copy of David in Piazza Della Signoria, climbing the Hercules statue in Florence naked, spray painting a work by Urs Fisher, and attacking artist Marina Abramowicz at a book signing by breaking a painting over her head. It certainly seems to be a dangerous time to be an artist, or artwork, around Florence. Despite racking up fines and prison sentences, Pisvejc appears undeterred by punishment, committed to his ‘artistic practice’ of damages.

His targets do not appear to be random, nor his actions without thought. In the case of The Porcelain Cube, Pisvejc appears to be imitating Ai Weiwei’s own artwork: Dropping a Han dynasty urn, 1995. In this work, Ai Weiwei drops an urn, the action recorded by three stills: held; falling; shattered. Just like the Porcelain Cube, the two-thousand-year-old urn is reduced to shards, the action permanent and irreversible. While the Porcelain Cube could be reproduced, the Han urn was consigned to history, along with its makers.

It is fair to say that neither artists would appreciate their art being destroyed. Not Ai Weiwei, who condemned the action of Pisvejc, nor the Han dynasty craftspeople. In some respects, the actions of Pisvejc and Weiwei appear rather similar, both destroying an artwork without the consent of the artist; acts of destruction which have artistic and historical significance, warping the meaning of the artwork for their own purposes.

However, Ai Weiwei’s destruction is displayed in his current exhibition in Florence, while the Porcelain Cube is replaced by a print of the sculpture still standing. Ai Weiwei’s destruction is elevated as art, Pisvejc’s condemned as vandalism. Is it ownership, not consent, which distinguishes the artists’ actions? This begs the question of whether ownership entitles an individual to the destruction of an artwork. Legally yes, but ethically it is more complicated. While Ai Weiwei owned the Han dynasty urn, the expectation of ownership of artwork is still one of safeguarding. Look at the Fitzwilliam gallery in Cambridge for example, which houses hundreds of stoneware ceramics, many unremarkable, behind glass, kept far from risk of destruction. Even in people’s homes, art is placed on shelves, out of the reach of children and pets, or hung on walls in glass frames, shielded from the elements. Further, an object like the Han dynasty urn belongs to China’s cultural heritage, which is owned by all. Certainly, by smashing the urn, or any artwork, Ai Weiwei subverts the expectations of art ownership and its moral expectations, destroying a piece of cultural importance.

“Weiwei’s act of destruction is part of his commitment to challenging oppressive systems of power”

But, this is exactly what Weiwei wanted to do. The urn is an emblem of a Chinese culture founded on history. In smashing the vase, he symbolically destroys the precedent set by history, calling for cultural and societal change. His action challenges the idea that when something is old and historical, it is valuable, important, and good. In destroying it, he calls for a re-evaluation of value. Referencing the destruction of antiquities under chairman Mao, he claims that the old culture must be dropped, and a new one ushered in. The action itself has power: the shock of destruction and its subversion of norms of art ownership a radical act. Pisvejc’s destruction has the same shock value, but none of the cultural meaning: the Porcelain Cube is neither historically significant (yet), nor culturally emblematic. Rather, the Porcelain Cube itself was already a subversion of traditional porcelain making. His action is therefore without a successful or obvious point, beyond the act of vandalism itself.

Art should never be destroyed without point or purpose, as art should be made with a purpose. Ai Weiwei’s Destroying a Han Dynasty Urn, while a radical and destructive action, is reflective of the artist’s commitment to activism. The artist’s investigation of government corruption and cover-ups, notably the death of students due to earthquakes in the Sichuan province, has led to him being beaten, doxed, and detained by the Chinese government. Destroying a Han Dynasty Urn is just one part of Weiwei’s continued commitment to challenging oppressive systems of power in his art and life. He destroys the old to call for a better new: if we always safeguard the old, what room do we leave for change?